Setting risk appetite: 5 approaches from practitioners

As risk leaders attempt to achieve the right balance of detail and simplicity in their risk appetite statements, is it better to set appetite for individual risks or broader categories of risk?

While defining appetite for individual risks may enable a more granular approach to monitoring and reporting, it could be impractical to uphold the amount of risk appetite statements this would require.

How, then, are risk leaders setting risk appetite, and what benefits do their various approaches offer? Below, we’ve highlighted a cross-section of five practical approaches practitioners in our network have adopted.

1. Connecting risks to impact categories

One organisation is using a modified version of the 5x5 impact-likelihood matrix – a standard visual in many risk reports – to anchor their risk appetite..png?width=618&height=348&name=Graphics%20for%20setting%20risk%20appetite%20blog%20(1).png)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Graphics%20for%20setting%20risk%20appetite%20blog%20(1).png)

This modified risk matrix plots 10 “impact categories” (five quantitative in nature, five qualitative) instead.

Each impact category has an appetite score of hungry, balanced or cautious. As an example, Safety would be attributed a “cautious” score, meaning very little risk (if any) should be taken.

In this system, risks are scored against their primary impact. So, whenever a risk is added to the risk register, it is associated with its biggest impact category, and this helps determine the overall appetite for the risk itself.

“The appetite for a majority of our impact categories is balanced, creating a lot of variance for what is considered acceptable risk-taking within the business. Our next step then is to be less vague about what each of the risk appetite settings mean.”

Head of risk from an FTSE 100 organisation

Risk Leadership Network member

Where does this information come from?In recent risk appetite collaborations we facilitated for members, practitioners in our network agreed that setting appetite is only useful for the business insofar as it enables the practical application of good behaviours. This article captures a variety of different approaches members have taken to anchor their risk appetite to specific principal risks or wider risk categories, as shared in bespoke virtual meetings. To get involved in future workshops and meetings, book a discovery call here. |

2. Defining "risk posture" rather than appetite

At another company, risk appetite is set in a top-down process for principal risks, as opposed to risk categories. Based on an assessment of both likelihood and severity, a “risk posture” of conservative, neutral or adaptive is defined for each principal risk.

.png?width=1050&height=700&name=Setting%20risk%20appetite%20(2).png)

Posture vs appetite

Posture could be better described as a framework for risk-taking behaviour in the business, instead of a set of limits.

Posture and reporting

Posture influences, among other things, how that risk is reported. For example, if a risk has a conservative posture, this means the audit committee wants more information about how the risk is being managed. This methodology drives some types of risk information up to the enterprise level more than others.

Posture and downside risk

A “conservative” risk posture is not always mutually exclusive with downside risk. In fact, an opportunity could be associated with a conservative posture, which would simply mean that the board and audit committee want more oversight. This would, in turn, increase the regularity of reporting.

One organisation has different “levels” of risk, which include parent (or principal) risks at “Level 1” and child risks at “Level 2”..png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Graphics%20for%20setting%20risk%20appetite%20blog%20(2).png)

.png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Graphics%20for%20setting%20risk%20appetite%20blog%20(2).png)

Currently, appetite is defined both qualitatively and quantitively for each of the business’ Level 1 risks, while Level 2 risks that sit beneath them are automatically assigned the same appetite.

Key risk indicators (KRIs) that sit behind each Level 1 risk, to monitor whether they are inside or outside appetite, are derived from existing key performance indicators (KPIs). According to the practitioner, utilising existing metrics breeds an “in-built” urgency to conform with tolerance levels.

4. Looking beyond principal risks

Some companies take a very different approach. One member organisation has 15 risk appetite statements that are not linked to any principal risks.

This approach is based on a simple principle: risks may change, but the business’ appetite for them shouldn’t.

.png?width=1050&height=700&name=Setting%20risk%20appetite%20(3).png)

Under each of their appetite statements, a definition is assigned to the one category of risk that the business may face. These definitions break down into three types:

- Risks we won’t entertain;

- Risks we’ll mostly avoid; and

- Risks we want to see less of.

In accordance with these definitions, investment and resources are committed to manage risks to the level set out in the risk appetite statement.

5. Establishing category-specific thresholds

One company has made subtle shifts to its appetite to signpost where more risk can be taken, and where greater caution should be applied.

“It’s important to consider the ‘end use’ when setting risk appetite. Given the nature of our business, employees are naturally risk averse.”

CRO at a FTSE 250 organisation

Risk Leadership Network member

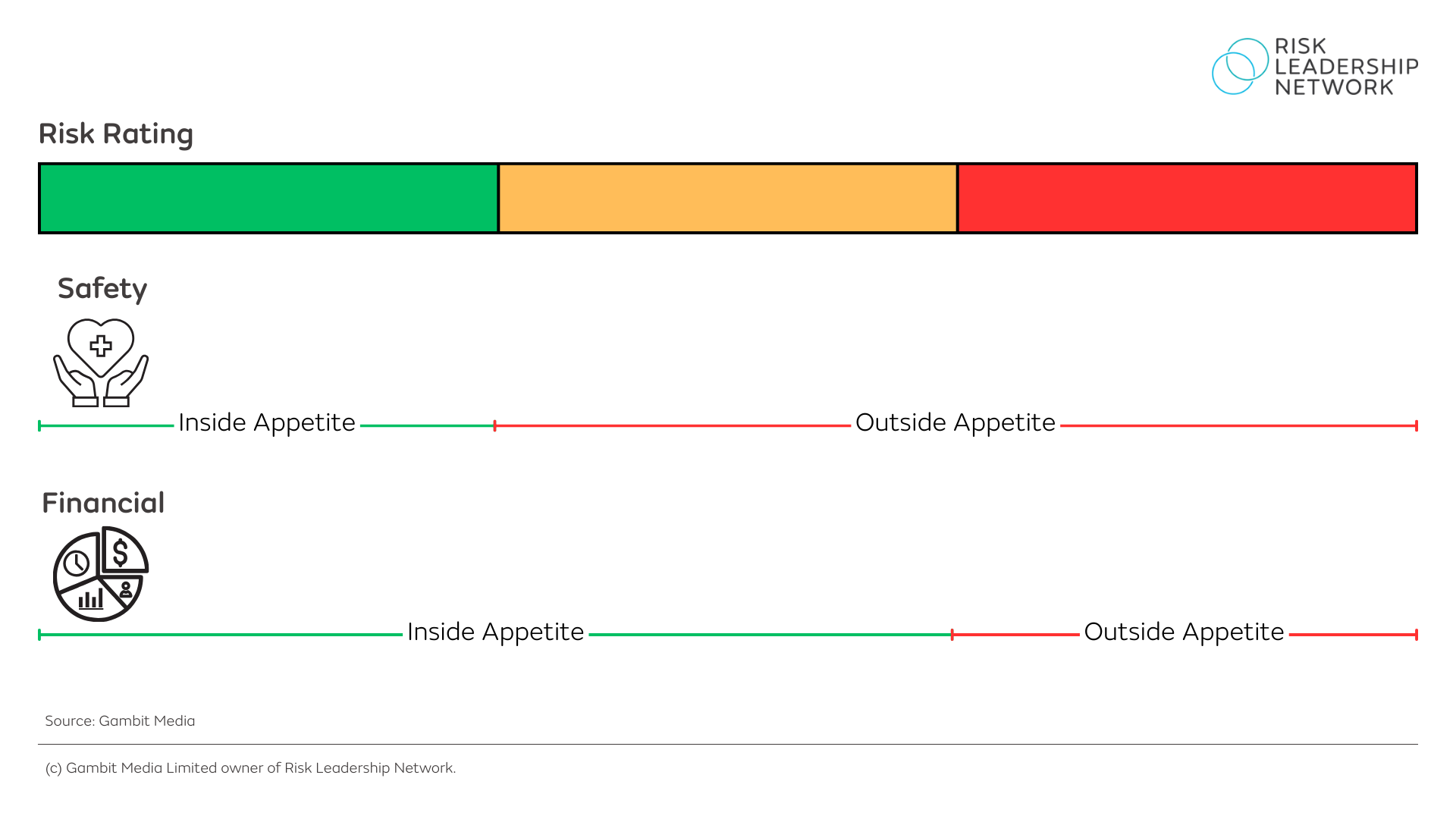

For each of the eight categories under the business’ risk taxonomy, different thresholds have been set for what is tolerable. This ultimately breaks down into a three-tier traffic light system, with risks either being marked red, amber or green..png?width=1920&height=1080&name=Graphics%20for%20setting%20risk%20appetite%20blog%20(4).png)

Where to next?

Share this

Related posts you may be interested in

How has risk appetite evolved in the past 3 years?

What is risk appetite and how do you implement it?